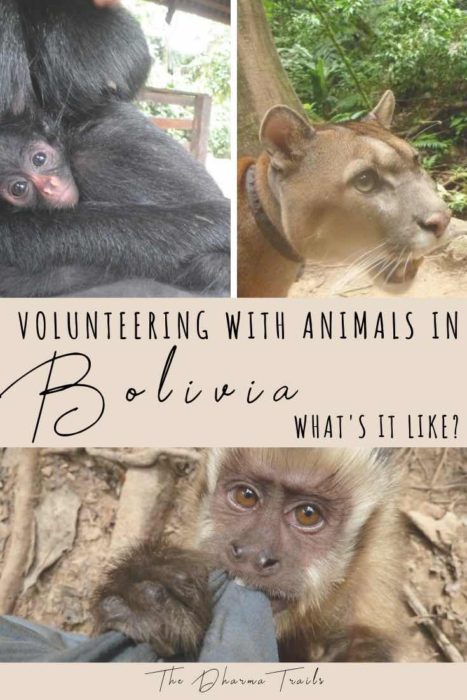

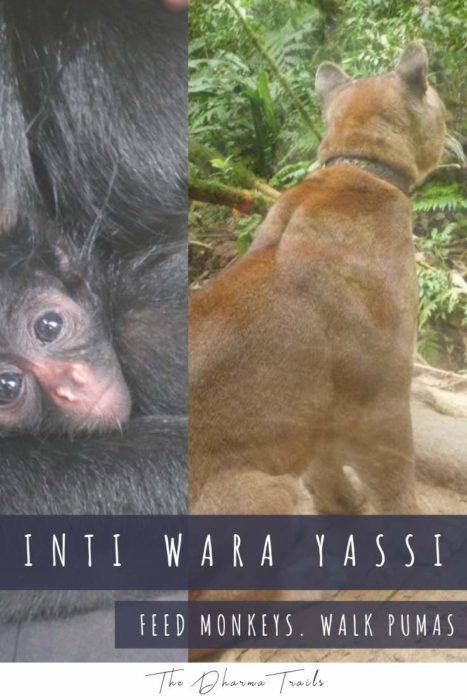

Parque Machia (Machia Park) is a protected area of the Bolivian jungle, just north of Santa Cruz. Inside the park is the Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi (Inti Wara Yassi Community [CIWY]). An organization that cares for mistreated animals from various backgrounds. It is an animal sanctuary that focuses on the treatment and wellbeing of monkeys (mainly Spider Monkeys and Capuchin Monkeys).

The park does however have a few larger animals, specifically pumas.

This post will give you an idea of the kinds of experiences that you can hope to encounter while visiting Parque Machia. This was a volunteering experience so keep in mind that it is very much a working sanctuary and everyone’s experience and take on the place will be different.

Table of Contents

How to get to Parque Machia

- Cochabamba is the main town closest to Parque Machia

- This can be reached from La Paz by bus (takes about 7 hours) check with your hotel or hostel about bus timetables

- From Cochabamba you can take a mini van for another 5 hours to get to Parque Machia

- There is a small town by Parque Machia called Villa Tunari

- You can walk across town in about 15 minutes

- Parque Machia is well know in the area so the locals can easily guide you to the entrance

Volunteering quick facts

- You have to pre arrange your volunteering experience at Parque Machia prior to turning up (as volunteering positions are limited)

- You have to pay to volunteer (this is to help run the facility itself)

- There are different time slots for volunteering experiences (the minimum being 2 weeks)

- There is different kinds of “wildlife” in the park though the ones dedicated to the “minimum 2 week volunteers” are normally monkeys, birds, turtles (the smaller, safer animals)

- The larger animals (bear, pumas) are reserved for those volunteers who do longer stays (3 months). It takes more training etc to deal with these larger animals.

- The accommodation is rough (you can check for eco accommodation alternatives)

- You will likely get bitten by a monkey (even if you don’t work with the monkeys)

- You will be really put to work (we carried bags of rock and sand up hills to build new enclosures)

- Jungle flies are vicious, and you will likely be bitten numerous times

- You will meet some amazing people

- Drinking every night is a must

- It will truly be a life changing experience that you will not forget

the good kind of animal tourism?

Initi Warra Yasi at Parque Machia is regarded as a recommendable sanctuary by WASP International (World Animal Sanctuary Protection).

This organization sets standards with which sanctuaries should be complying. Animal tourism is a delicate business. Many places around the world that claim to be eco friendly animal tourism attractions are actually doing more damage than good. To learn more about which types of animal tourism, here.

The park (parque)

The site of young volunteers in ripped clothing and gumboots, drenched in sand-fly welts and monkey feces was a little off-putting at first glance. They were really put to work. I had been traveling for six months through South America without any real form of responsibility let alone a job, or even caring for another being, though I was sure the experience would do me good. It was predominately a monkey sanctuary, but the thought of potentially working with the puma of Parque Machia was definitely on our minds.

Pre-used wire mesh, wrapped into cages, held various sizes of monkeys with varying psychotic tendencies and health concerns. The stench of urine and freshly tossed papaya stank the humid air. Volunteers walked past with monkey bites (covered in stitches and purple antiseptic ointment). All of them, became a statistical nightmare. This however did not deter the smiles of the feces-cleaning, monkey victims. This led me to believe that it would be an enjoyable/humbling experience (which it was).

My task

Everyone was designated different tasks during their stay at Parque Machia.

Mine was to feed the ‘wild’ monkeys in the jungle behind the reservation area. My mission was to decoy these wild monkeys; preventing them from stealing the food supplied to the human-dependent monkeys. This, in a sense, deemed the ‘wild monkeys’ equally dependent on their daily three meals, provided by yours truly. The system was flawed, but it seemed out of my jurisdiction to amend, so I continued.

I would walk a large bucket of fruit and vegetables thrice daily into the Bolivian jungle towards a waiting pack of vicious primates.

The Monkey Mob

‘Celine’ was the Alpha male. A wretched, scar-faced monkey, unfazed by humans and unpredictable at the best of times. He was also the cause of most battle scars amongst the volunteers at Parque Machia.

Each day I would have stand-off interactions with him and his primal clan. Each time I feared the thought of his vile fangs piercing my skin or collapsing an eye. He was a truly mean being. For the first few days, he would drop unknowingly from the canopy onto my back and his small (but powerful) hands would pry the bucket’s strap from my grasp. His hot breath dripped from his dirty mouth across my neck, sending fear down my spine to the fingertips grasping his meal. This is why I would drop the fruit.

He would take the bucket and bang it around on the floor until those bananas were in his little, devilled grip.

It wasn’t until I talked about my dilemma with another volunteer that the notion of a double banana decoy became apparent. I was dealing with a mob. A gang of thuggish primates, running mayhem through the surrounding jungle.

Monkey Bribes

Not only was I paying off the gang to leave the reserve and its inmates alone, but I also had to bribe the boss-monkey to allow me into his jungle to execute the transaction. This is life at Parque Machia .

I found the whole scenario exciting and was quickly becoming part of an underground jungle scene. It was a dark, green world full of instinct and fear. Each day the personalities of the individual monkeys became more apparent.

Some were outgoing and very vocal. Some pretended to be fierce though would shrivel if I second glanced them and then there were the timid, shy monkeys who ate the scraps of the dominants, once they had cleared.

It was a fascinating world. Once I realized how it worked I began to sit and observe from various distances. Hours would pass as I sat in the jungle, rubbing mud from a nearby creekbed over my skin to prevent fly bites, observing monkeys, birds, lizards, ants, everything around me became one and connected. I was the jungle.

The morning after

The days always ended at Parque Machia in a congregation of horror stories and beer at the camp’s 20ft long wooden table. There were many volunteers from the United States, but a surprising number were from the UK and a few from other European counties.

Inevitably, there was a new bite, infection, or attack at each meeting and after a few drinks, the stories became hysterically vivid.

My ‘Celine’ encounters never grew old, as each day presented some small adaption to the proceeding day’s tale.

The drinking would continue steadily most nights however on occasion a specific team (monkey, bird, or other) within the park would throw a fundraising party of some description. This involved a couple of 20Litre drums of cheap, Bolivian vodka, some 96% alcoholic whisky, and a themed dress. The first of those parties that I attended was called the “come as your animal night” with the intention that people caring for birds would dress like birds, the same for monkeys, and so forth. The reality was that we were all animals and proved it, several hours into the ‘jungle punch’.

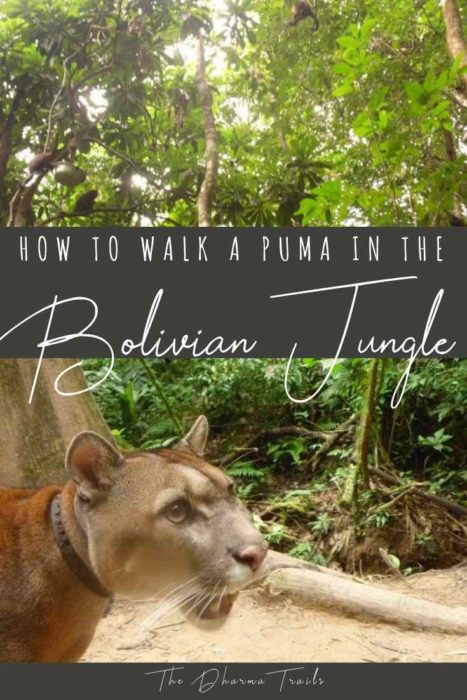

This party was the reason I had my encounter with the Parque Machia puma. The long-term volunteers who were actually on puma duty (you had to commit to at least 3 months to handle the puma – in order for it to become familiar with you, as these things take time) were too hungover from the party. I just happened to be up and about, so they took me, in a groggy state.

Preparing to see the Puma

The puma is probably one of the main attractions for volunteers at Parque Machia yet 95% of them never actually get to see him or even come close. This was my chance.

I thought. “Sure, what’s the worst that could happen?”

So I follow a scruffy, yet extremely fit, young guy, named Iri, into the food storage room and collected several pounds of raw chicken. The site of it all made my stomach churn.

En Route

Iri was in a rush. “Let’s get a move on, we’re already late. He gets angry if we’re late.” This rattled me a little, but I continued to quickly pack the chicken.

I follow Iri’s shaved head toward the back of the sanctuary and we began our trek down an unmarked pathway; leading us into the jungle. The mud seemed to grab my gumboots, just enough to make the progressive steps painfully tiresome. The sheer gradient of the track threw my post-partied inner balance off the scales.

After nearly an hour of the military-paced climb, through the thick jungle, taking various color-marked routes. I thought “there is no way I would ever find my way back.”

I suggest a breathing stop and he abides, though is unimpressed at my lack of stamina.

“So, I meant to ask you, Iri. What are we actually doing today? I mean, what does ‘help out with the puma’ involve?”

I am panting like an old man.

“Well, I guess we clean out his cage and we walk him through the jungle and feed him and make sure he don’t have no problems.”

“Yeah cool, how do you walk a puma, I mean what kind of… ‘eh, you mean on a leash?”

“Kind of, it’s two ropes, I have one, you have one, and you will see what I mean.”

I guess that’s all the training I need to handle a potentially lethal animal then. Ok, I can deal with that, I thought.

“We must call out to let him know we are coming.”

His voice is seriously stern.

“We do not want to make him feel as if we are sneaking up to his cage, for then he will be aggressive.”

The puma

We step down some rotting steps, towards a cage the size of a typical two-bedroom house. It has logs, stretched across its width (for puma climbing), a platform covered in straw, and an adult, male puma on alert. The thing is huge; it’s the height of a German Shepard with paws like dinner plates. His eyes pierce right through my exhausted body and in a split second he has figured out my life story and how he plans to take me down.

Walking the Puma

“Ok, because you’re new and he doesn’t know who you are, he may give you some attention, but he’s just testing you, don’t be afraid, he will sense this.”

The seriousness in Iri’s voice continues to fuel my anxiety. Iri continues toward to cage door and slides open a release latch. The puma moves slowly toward the opening, maintaining a visual lock on my position.

“Just stay behind that tree stump over there, he can’t reach that far.”

So I moved. Quickly. The puma was then clipped to a run-line between two trees where he continues to maneuver with extreme precision, emphasizing the muscular definition along his back and shoulder blades. He sniffs the air with force and from 10ft away determines my every move from the previous night’s activities.

Iri attaches a rock climbing clip to the puma’s collar from a thick rope around his waist. I have a spare rope wrapped around my waist and a backpack with a knife, a bottle of water, and some crackers inside.

The Pounce

The puma, obviously aware of the procedure, begins a slow walk in front of him, back up the pathway from which we came. He was clearly displeased with the additional, new human. The frustration in his body language and grunts of uneasiness for the first five minutes made this clear. It creates an un-measurable tension.

The puma stops. He sits forward but looks back at me. Then tilts his head, slowly. Time stops.

“Ok so, he might try to…”

Without a chance to process the rest of Iri’s statement my body is cloaked in primal power. The forceful strangle of the puma’s legs wrapped tightly around the once-pinching rope. The pressure is immense and it hinders my circulation.

His ribcage indented between the grooves in my own, forcefully taking the wind from my lungs.

Muscular arms crunched the sides of my neck. The raw power seized my ability to move. I stood helpless.

His fangs were prying into my face with precision and he forced his hot breath into my tired eye socket. I am now lodged inside the creature’s mouth.

Another split second passes; the alarms and rattling in my head surpass the pain of the overall crushing pressure. I’m suffocating under the puma’s touch. I am overwhelmed by the intense power enclosing my being and lose the ability to act.

I hear Iri screaming, but he sounds so far away like he’s been engulfed by the jungle. He’s muffled.

“So this is how I go. Wow. I didn’t see that coming.”

Then, after what seemed like hours, the pressure eases. The fangs released with an instantaneous endorphin of relief.

“Oh my God, I’m so sorry I’ve never seen him do that before, he actually jumped on you, holly sh*t!”

“Yeah, he really did.”

Jungle fun

For the remainder of our walk, there was a surprisingly calm atmosphere between the three of us. We were completely submerged in nature and the order had been restored. There was no doubt who ruled the jungles of Parque Machia.

The fangs pressing my face never actually pierced the skin and only left bruises at the pressure points, though the dewclaw (the small un-retractable claw on the side of the paw) did actually cut along the back of my head, deep enough to draw blood and leave a scar.

Overall, it was just part of the experience.

The animals are in cages. But they are still animals.

I had a ball interacting with the different species over my few-week stay (including the humans). It really was a fun experience, despite the hard work and conditions. I would recommend Parque Machia to anyone looking for something memorable.

More information on volunteering

Everyone’s experience will be different at Parque Machia. However, most of the people I have met that were lucky enough to participate were very happy with their time and overall with the way that things are done.

If you want some more information on the park itself. This short video explains it well.

Eco travel tips

Here are our eco-travel tips for making the most out of the experience:

- Drinking water is a big one. As you cannot drink from the tap here, a lot of people resort to buying water bottles. If you’re going to buy plastic water bottles, it’s best if you get a couple of large (5 litre) containers and just pour into a reusable bottle to take with you during your volunteering hours. – Alternatively look at bringing a water purifier.

- Preventing insect bites. Parque Machia asks you not to use insect repellant. This is to prevent negatively impacting the animals you will be in contact with. So, consider natural alternatives. Moov with melaleuca oil could be a good one. Otherwise, I used mud while in the jungle. Paste it on! It really worked.

- Be careful where you eat. There was a restaurant in town that was selling armadillo. This is a no-no. If you are volunteering with the animals, you’re already a step ahead by supporting a good cause. Just be careful not to support the wrong cause while you’re at it.

- Go natural. Your going to be in a pretty rough place, with not much in the way of options for buying things. You don’t really need to worry about looking good (as everyone is constantly dirty). It’s best to use natural products (toiletries) as you will be in contact with animals. Here’s a list of our favourites.

- Support the locals. The town is small and quiet. There are a few nice local restaurants. The food is good. Try them out instead of eating instant noodles.

Like This Article? Pin it!

Looking for more destinations in South America? Check out our tips on the best things to do in Easter Island.