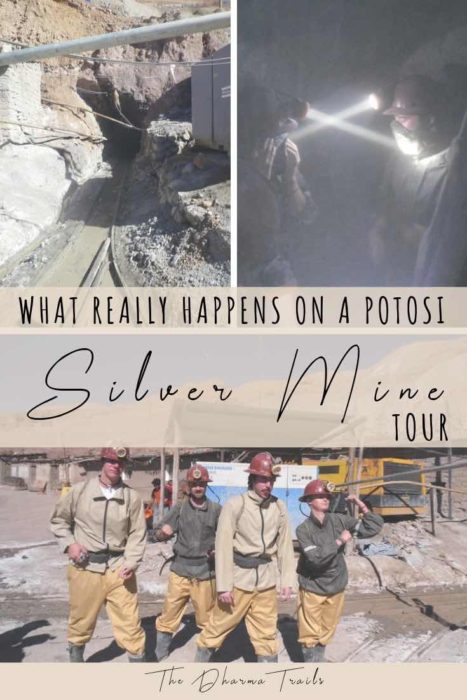

At 4,090m (13,200ft) above sea level, the air in Potosi is thin and cold. This mining town is on the South America backpacker trail, drawing in tourists that want a little thrill and adventure. But is the Silver Mine Potosi ethical to visit? Here’s what you need to know before you go.

Table of Contents

Silver Mine Potosi History

The silver mine began like most colonies, with the pillage of local amenities sometime back in the 16th century. During this time, tens of thousands of African slaves were brought and forced to extract the mountain recourses, quickly turning Potosí into one of the wealthiest cities in the world. Meanwhile, the mine killed around 30,000 of its workers, deep within the mountain, which is believed to have the devil’s presence.

Now, the mountain has around 100 different operational crews working various time shifts at various depths within the Swiss-cheese, maze of caverns and rock face. It is extremely dangerous work conditions and without the ‘health and safety’ regulations of most westernized countries.

Modern miners, before each shift, offer a token of gratitude to devil statues that guard the entrances to every mineshaft. The superstitious values are not taken lightly.

What does the Silver Mine Potosi Tour Involve?

Most tours start with a stop at the base of the infamous peak at the miner’s supply street. They stock large potato sacks of dried cocoa leaves with the appropriate chewing adhesive, various bottles of cheap spirits with a focus on the locally produced white-whiskey advertised at 96% alcohol, locally branded cigarette packets, and all the essential ingredients for the creation of dynamite.

The Silver Mine Potosi Tour guides usually request the tourists to purchase all of the above for the miners. It is in addition to the tour cost and though it’s not expensive, it makes you wonder if the miners relied solely on the donation of tourist’s dynamite to perform their extraction works.

The Silver Mine Potosi Tour Experience

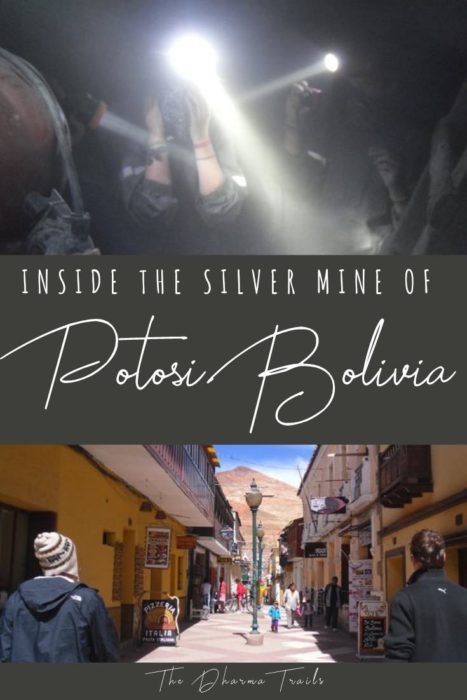

When you enter the mines, it’s darkness. Stepping over railway tracks the guide leads you deep into the abyss. Natural light diminishes at an astonishing rate and you become engulfed by the darkness. The only light ray is the one projecting from the plastic helmets and with each step deeper into the mine the air thickens.

A wrapped bandana covers my mouth and nose. Condensation builds on the inside and coagulates with the dust creating salty thick saliva, gripping the extremities of my tongue. A horrible taste of confinement amplifies my growing sense of claustrophobia. I feel like I am eating my way into the mountain. The mood thickens with the dust. Tension rises and the ceiling drops. The confinement intensifies. Breaths are short and inefficient. Smiles are subtle through fear. The darkness grasps tight. This might not have been the best idea.

The surrounding earth shudders violently as blasts in mineshafts close by create a rustle of ceiling rock and emotional instability. Deafening blows shoot dust through the tunnel at an alarming rate. It is dry and sour, with a chalkiness that can cause feelings of suffocation.

Climbing a rickety wooden ladder into a small cavern the tour continues with a sense of chaos. Watching cautiously as the drilling crew place dynamite sticks carefully into each drill hole, floor to ceiling around us. There is a feeling of insanity. How are we going to get out of here in time? There must be fifty sticks of dynamite surrounding us. We are inside an explosive pincushion. The guys forcefully press the last couple of sticks down their respective slots. “Oh shit. He’s going to light them. Ok now! Run!” What! This is crazy!”

The rock walls/ceiling are covered in arsenic materials, and when you are crawling through tunnels, you are bound to get some on your hands/body.

The grueling 30-minute trudge back through the humid mineshafts breaks with the sight of daylight. A godsend. A release from the devil’s grasp. For tourists, it’s like they will never again enter the mountain but for the rest of the miners, it was merely another dark day in their existence.

Is it ethical to visit?

With over 8 million miners being killed over the last 500 years, they are dangerous to be in. Most silver mine potosi tours, although providing the miners with gifts of tobacco, alcohol, and dynamite, also include a component where the tourists can blow up dynamite during the visit.

This is not only unsafe for tourists, but for the miners that are having to work there each day. With virtually no regulations and workplace health and safety, who knows what the ripple effect of that tourist dynamite will be.

The Silver mines of Potosi are an insight into the dark side of Bolivian life. Miners are held captive, within a world of darkness and superstitions with statistically short lives ahead of them. Their life expectancy is generally late 20s to early 30’s. But there are other ways to gain insight into the mines, The Devil’s Miner is a documentary of a 14-year-old boy and his 12-year-old brother that worked in the mines.

Eco travel

Eco travel is a great way to get around. Find out more about eco travel and eco accommodation to improve your trips sustainability.

- You’re up high. Stay hydrated. You cannot drink the tap water, so buying water is essential (unless you bring your own filtering kit). Buy large (5L) bottles and top up your reusable bottle.

- Avoid drugs (prescription pills). Altitude sickness is a real thing. I’ve felt it. But, it is treatable and avoidable. Use the local knowledge and chew coca leaves (mixed with bicarbonate powder), it reduces the feeling of altitude sickness and does not benefit the pockets of Pharma companies. It also reduces the need for small plastic bottles that contain your altitude pills.

- Rubbish everywhere – be prepared to pick some up. Unfortunately, Bolivia is riddles with rouge plastic bags. Be prepared and pick some up while you’re there! There are plenty of alternatives to plastic bags!

More articles on South America

- Volunteering at Parque Machia

- Best things to do in Easter Island

Like This Article? Pin it!